Learn all about first and last frost dates, and hardiness zones, and how they can impact the success of your growing season.

In vegetable gardening, a successful season involves a wide variety of factors, including seed germination, cultivar hardiness, pest and disease loads, rainfall and storm severity, access to direct sun, pollinator density, and sometimes just good old-fashioned luck.

But at the root of it all, there’s the ambient environment. When does it get warm enough to start growing crops? What kinds of plants are suited to the typical weather patterns in your area? When does the growing season end?

These questions and more can be answered by knowing your frost dates and plant hardiness zone.

First and Last Frost Dates

These dates refer to the approximate time of year in your area when the last hard frost in spring occurs and the first hard frost in the fall occurs. Let’s take a closer look, moving from the beginning of the growing season to the end in the U.S.

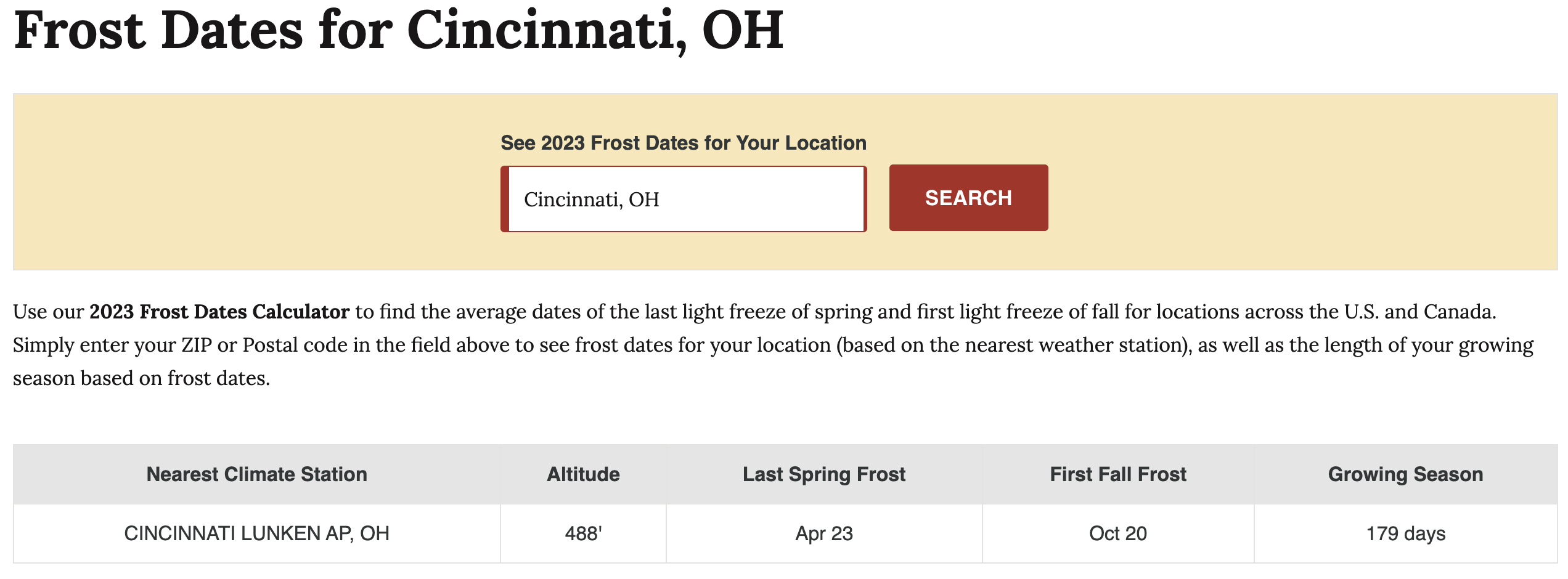

The Almanac (a.k.a., the Old Farmer’s Almanac) is the gold standard source for locating your frost dates. Here are mine:

This resource is invaluable for seeing your frost dates at a glance, as well as the length of the growing season. These dates are based on historical climate data for your area, so while they’re not precise — and definitely can’t account for the wild variability we have from year to year — they’re good guidelines to use when planning your garden.

Knowing your frost dates and the length of your growing season will let you calculate whether the vegetable you want to grow will have enough time to fruit and ripen before the cold weather kills the plant.

It can also help you decide whether to take other steps, such as starting seeds indoors to give a crop a head-start on growth.

Last Frost Date

The last frost is the general time frame you can expect for the last hard frost to occur in your area at the start of the growing season.

This is important to know because many plants will not seed germinate or thrive outside as starter plants in the cold temperatures involved in a hard frost or light freeze. There are exceptions, of course: many brassicas (kale, broccoli, cauliflower) and alliums (garlic and leeks) thrive not just in frost, but also in outright cold temperatures once established.

But other summer favorites, such as tomatoes and cucumbers, require stable, warm weather to survive and thrive.

In past decades, my last frost date was April 15th, but I regularly pushed those limits by planting my gardens by the end of March, with protective covers on standby just in case (e.g., cages and sheets for my tomatoes) because springs were reliably mild.

But for the last ten years or so, the last frost date has been creeping later into the month, and not only that but also we now have damaging cold and snow that lasts well into April.

First Frost Date

At the other end of the growing season, there’s the first frost date, which is the approximate day you can expect the first killing frost or freeze of the season to occur.

What is the impact of the first frost date on plants? Some warm-hardy plants will actually survive the first frost, but they’ll stop fruiting. Tomatoes are a good example of this.

Tomato fruit needs warm weather to ripen, and once the weather turns chilly, the plants might look okay but the green tomatoes on the vine simply won’t mature, and existing flowers won’t produce new tomatoes. (But don’t let those green tomatoes go to waste: they’re amazing pickled as well as famously fried.)

Other plants undergo a structural breakdown during the freeze-thaw process: you’ll go out to the garden the afternoon after a heavy frost only to find goopy piles of leaves and stems.

But, as mentioned above, some plants continue to thrive in the cold and my gardener’s curiosity tests every vegetable variety I grow to learn their limits and extend the growing season. Broccoli, leeks, and carrots (although they lose their greenery) do well. Kale survives well into winter. And even — surprisingly! — flat leaf parsley does quite well in cold weather (although not through wet snow).

Plant Hardiness Zones

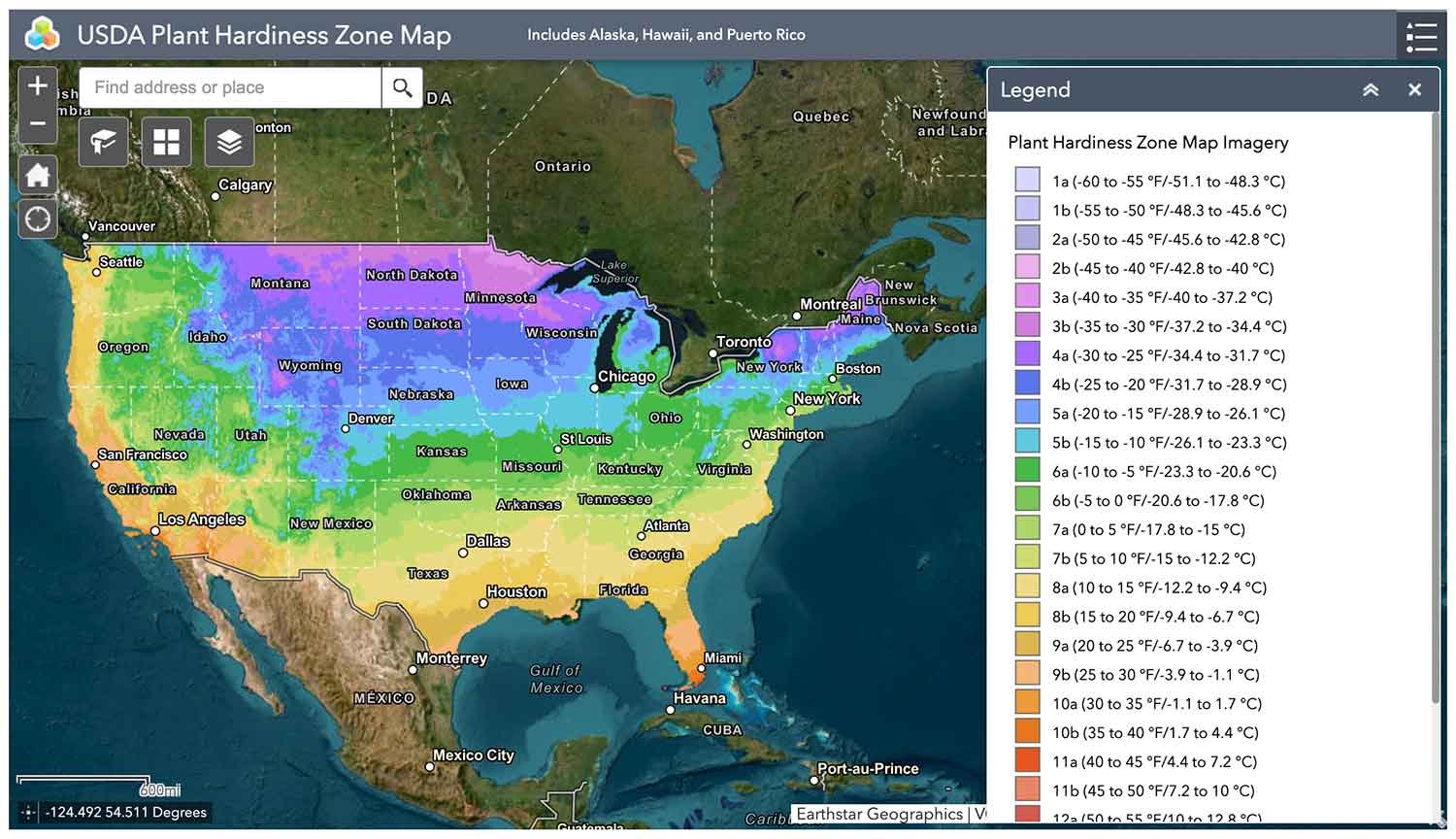

Another guideline for knowing what plants will grow well in your area is the USDA’s Plant Hardiness Zone Map.

This is a visual map of the U.S. that has been color-coded into zones according to average minimum winter temperatures. Here’s a downloadable PDF of the map (freely available from the USDA).

The USDA also has an interactive map on its site that allows you to zoom in on your own location and determine exactly which “half zone” you live in (i.e., the “a” or “b” portion of each of the 11 numerical zones). Note that the map is best viewed on desktop as it is quite large and detailed.

The interactive map is pretty cool, as it goes down to street level. I’m in zone 6b, but zooming in closely shows that zone 7a is just down the road a bit. This is useful to know because it means that I’m likely impacted by the 5º lower winter temperatures of zone 7a.

How to Use the Hardiness Zone Map

So, for the typical backyard vegetable gardener — and I count myself among that group — knowing the average minimum winter temperature of where I live doesn’t directly help me be a more successful vegetable grower, because the majority of what we grow are annuals — greens, radishes, beans, tomatoes, bell peppers, cucumbers, squash, etc. — which must be seeded and grown anew every year.

However, the map comes in handy if you enjoy growing perennial flowers, herbs, or fruit trees/bushes/vines. Or if you live in a warm-winter climate where minimum temps stay above freezing, giving you a much broader selection of what — and when — you can grow.

But even here in the cold Midwest, plants like chives, thyme, sage, tarragon, and oregano survive the winters in my zone. While they drop their leaves and recede each winter, they do return each spring.

Knowing which plants are 6b-zone-appropriate ahead of time allowed me to pick permanent spots in my yard where they could thrive undisturbed for many years to come.

Before the internet, seed sellers used to indicate the plant’s appropriate hardiness zones right on the back of their seed packets. That practice has largely fallen out of use because seed sellers can now include even more details about their plants right on their e-commerce store pages, and they don’t have to worry about squeezing it all in fine print on a 2″ x 3″ packet.

I hope this information has been useful in helping you plan your herb and vegetable gardens this year. As I type this here in mid-March, a snow squall is passing through and sticking to my chive plants, which emerged early because of the 80ºF weather we had in February.

I’m eyeing my last frost date very eagerly and impatiently!

Welcome! I'm Karen, Chief Gardener, Tool Cleaner, Tomato Pruner, and Cabbage Worm Picker-Offer.

Welcome! I'm Karen, Chief Gardener, Tool Cleaner, Tomato Pruner, and Cabbage Worm Picker-Offer.

Leave a Reply